Twenty years ago we went to Castelli's, the most fabulous and expensive restaurant in Ethiopia, to celebrate our "first" wedding anniversary. Weren't we adorable?

And doesn't that antipasti spread look delicious?!

Happy Anniversary to my leap-day husband.

Monday, February 29, 2016

Friday, February 26, 2016

I Am Officially A Housewife.

I

mentioned that shopping – especially for durable goods – was a challenge to us

during our first few weeks in Ethiopia. This is how I described the duty-free

process in an e-mail message to my sister on June 14, 1995:

“Ever since

we arrived – seven weeks ago – we have been trying to acquire ‘duty-free

status’ which exempts us from paying huge taxes on imported goods. When I say

huge I’m not kidding: people who buy cars here often have to pay import duties

of 100%. We are eligible for duty-free status because we are foreigners working

for an NGO, but it’s not that easy. First, we had to get work permits, which

sounds simple enough, but for some reason J. had to get another entry visa,

despite the fact that he was already in the country and had an entry visa from

the Ethiopian Embassy in Washington, DC. After the work permit (Which J. had to

get but I didn’t, because I am officially a ‘housewife’…) we had to get our

residence permits, which took another two weeks. Then FH had to write a letter

requesting duty-free status for us, and THEN we had to write a list of all the

things we want to buy at the duty free store. Finally, today, we are able to

take our official list and letter down to the store and make our purchases.

It’s a good thing FH had a fridge and stove we could use in the meantime, or we

would be hungry and cranky people.

…I

don’t mean to sound like I’m complaining, because I’m not. We are very

comfortable here, just surprised at some unexpected requirements. …At most stores

here what merchandise they have isn’t available to the customers. Instead, they

will have one item on display, and if you want one you have to go to the

counter and ask a clerk to get it for you. The clerk fills out a list, and then

you pay for your purchases, and only then do you actually get your hands on the

goods. Thankfully, this is mostly not the case at food stores, or I would be

insane by now.”

Turns

out we didn’t get to the duty-free store for a couple of weeks, but we didn’t

let that stop us from using the oven:

“We

have begun to experiment recently with our gas oven, and have been pleased with

the results. The reason we’re experimenting is that the oven control has

numbers from 1 to 9 on it, and we don’t know what temperatures those numbers

correspond to. Also, we’re working with ingredients that are not quite what the

recipe calls for. We tried making cornbread last night with maize grits instead

of cornmeal, and it turned out to be tasty, if a little crunchier than usual.

…Bread is always an experimental proposition here because of the altitude:

we’re never sure if it’s going to rise properly. We’re going to try some banana

bread tomorrow, with bananas that we picked off the tree ourselves when we were

down country last week. Mmmm! We have found it quite challenging to light the

oven with a match. I am always afraid that it’s going to explode. But we are

going to buy a new oven soon, and we’re hoping that a newer model will be

easier to work with.” (June 14, 1995)

What

about groceries? We generally bought our food at the relatively expensive

markets that catered to foreigners; there was one just around the corner from

our apartment, and a couple more across town. One of our favorites was the

7-11.

|

| At the "7-11" on Jimma Road. The clerks wore authentic convenience store uniforms. |

“We

just bought another can of oatmeal, so we have been splitting our breakfasts

between oatmeal and scrambled eggs. J. makes a really nice scrambled eggs with

cheese. Eggs cost 40 centimes apiece, that’s about 7 US cents each, so it’s

comparable to home. But they aren’t sold in dozens. Instead, you choose your

eggs from a big flat, and they put them in a paper bag for you to carry home.

I’m always worried that I’m going to smash them, but it hasn’t happened yet.”

(June 25, 1995)

Here’s

a picture of my sous chef at the kitchen table in our apartment, trimming up some

green beans for dinner. Pardon the mess.

Tuesday, February 23, 2016

One More Thing About Cheha.

There’s

one more thing I wanted to write about the FH/E project in Cheha before I move

on to a new topic. I mentioned earlier that veterinary services were part of

the program there – the people in that region were known as herders who relied

on their cattle both as a food source and for working in the fields. To keep

the animals healthy, it was essential to vaccinate them against malaria and trypanosomosis, diseases spread by the tse-tse fly that could weaken cattle, reduce milk production,

and eventually lead to death.

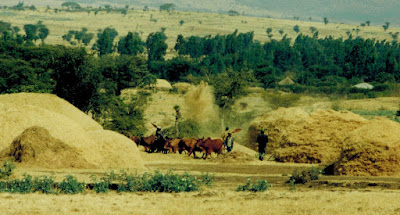

These photos weren't taken in Cheha, but they give you a good idea of what the local cattle looked like and how they were used -- in this case, threshing teff to separate the grain from the chaff.

The

head of the veterinary service for the Cheha project was Dr. Noda, a Japanese

veterinarian – or should I say, The

Japanese Veterinarian, because he was a legend. There weren’t a ton of Japanese

people in the country so he kind of stood out anyway. And, since he spent most

of his time down country, his Amharic was better than his English – which

earned him the love and respect of his Ethiopian colleagues. We were in awe.

Friday, February 19, 2016

The Election.

I mentioned a while ago

that anyone who knows anything about Ethiopia remembers that there was a

serious famine in 1983-85, but like many people our age that was pretty much

the only thing we knew about Ethiopia

before we agreed to move there for three years. So our first few weeks in the

country were a simplified but intensive course in the political and cultural

history of Ethiopia in the 20th century.

We had, of course, heard of Haile Selassie, the emperor who ruled the country in one way or

another for almost sixty years, from 1916 until he was deposed by

revolutionaries in 1974. We didn’t know much about the difficult decades that

followed, under the brutal regime of Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam and the

military junta that came to be known as the Derg

(Amharic for “Committee”). Mengistu and his cronies in the Derg abolished the imperial government –

most Ethiopians believe Mengistu executed the ailing Haile Selassie with his

own hands – and established a Marxist-Leninist system that nationalized land

and industries, resettled peasants, and aligned Ethiopia with the Soviet Union.

In their effort to quell political opposition, the Derg implemented a campaign of intimidation and murder that came to

be known as the Red Terror. The campaign lasted for two years, from 1977-1978,

and was responsible for the deaths of as many as half a million people,

including women and children. A missionary friend of ours remembers driving her

kids to school during these years, chatting away in an effort to distract them

from the dead bodies that were hanging from lampposts or lying in the streets

of Addis Abeba.

Instead of silencing

opposing voices, the Red Terror strengthened and consolidated rebellion against

the Mengistu regime. Resistance groups throughout the country – Tigray and

Eritrea in the north, Oromia in the south – organized insurrections against

local Derg strongholds. In 1989 (when

we were in college) the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TLPF) joined with

the Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement and other groups to form the

Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). As the EPRDF

advanced on Addis Abeba in 1991, the government collapsed. With help from the

US government, Mengistu and his family fled to Zimbabwe, where he still lives

in luxury under the protection of dictator Robert Mugabe.

By the time we arrived

in Ethiopia, the Transitional Government had written a new constitution and had

called for a general election to take place – in May 1995. Although Ethiopia’s

parliament dates back to Haile Selassie’s 1931 Constitution, this was the first

multi-party election in the country’s history. It was kind of a big deal.

International observers came from all over the western world, including – it

was rumored – former US President Jimmy Carter. There were more than 40,000

polling stations established throughout the country to accommodate nearly

twenty million voters. Four of the seven major political parties boycotted the

process; as expected, the EPRDF – which had been transformed from a military

force into a political coalition – won an overwhelming majority of seats in the

House of People’s Representatives. Meles Zenawi, who had dropped out of medical

school in 1974 to join the TPLF and had risen to become chairman of the EPRDF, was

elected as the first Prime Minister of Ethiopia. (He was re-elected three

times, in 2000, 2005, and 2010, and he died in office in 2012. But that’s

another story).

As newbies, we didn’t

have much of a grasp of the import of the election, and we didn’t know our

Ethiopian colleagues well enough to talk about politics back in those days. It

had been – and for many it still was – a life-or-death kind of topic in a way

that we couldn’t understand. (It became more real to us a few months later,

when one of our work colleagues was arrested for his collaboration in the Red

Terror. He would have been a teenager at the time. We never heard from him or

about him again).

One of my lasting

memories about the election is from an early visit to the Cheha site, where I

saw a printed handbill pasted up on the wall of a building. I couldn’t read it,

but I could see that there were several simple pictures of common household

items on it – a jebena (coffee pot),

a basket, a spoon. I wish to this day I had taken a picture of it. Curious, I

pointed it out to one of the project staff and asked him what it was for. He

told me it was a sample ballot designed for areas with limited literacy. Each

candidate or political party (I forget which) had been assigned a picture, so

if a voter couldn’t read the candidate’s name, he or she could still remember

to vote for the coffee pot. Brilliant. These days it’s easy to be cynical about

the democratic process, but I will always appreciate how intentional this

developing country was about ensuring the right to vote even for its most

disadvantaged citizens.

Edit 2/23/2016: Here's a link to an image of the type of ballot I described above. I don't read Amharic well enough to know which election this is from, but you can see the coffee pot, there at number five.

Edit 2/23/2016: Here's a link to an image of the type of ballot I described above. I don't read Amharic well enough to know which election this is from, but you can see the coffee pot, there at number five.

Friday, February 12, 2016

Down Country, Part Three.

You know how sometimes,

when you’re watching Antiques Roadshow, there’s a family story that goes along

with an object, and more often than not the appraiser has information that

undermines or completely contradicts the story? That’s kind of what it has been

like for me, comparing my memories of our trip to Cheha with the written

account that I sent to my sister at the time, more than twenty years ago.

First of all, it turns

out that I went to Cheha not once but twice in the spring of 1995 – the first

time with J. and Walter the Kenyan consultant, and a second time with a

videographer from FH International (because I was already an expert by then!?).

Here’s what I wrote about the first trip:

On

Monday and Tuesday (May 8-9) we drove “down country” to FH/E’s Cheha project

site. It was a really remarkable experience! We had to remember to take our

malaria medication, and we have to continue to remember for the next four

weeks. We spent three hours driving 110 km over bumpy, narrow roads, and those

were the good roads! But it was well worth it, since we got the chance to hang

out with project staff people and to meet and talk with some of the

“beneficiaries”. We were really impressed by our visit to a child-to-child

group. This is a group of kids who have gotten together to take over what had

been an FH demonstration plot, where farmers learned irrigation and

agricultural techniques. These 100 kids now come to the plot every day to tend

their plants, and when their crops mature they harvest the produce and, after

taking some home to their families (and increasing the family’s nutrition) they

sell the rest at local markets. These kids know more about gardening than I do!

Some of them were also given a goat to raise, and one little boy now has five goats

and is relatively wealthy for a ten-year-old. The best part was realizing that

these kids are learning things that their parents were never taught about

health and nutrition and sanitation, and that gives them something else that

their parents have little of – hope for the future. They expect something

different out of life.

The second visit – the

one I didn’t remember – I read about it in an e-mail message that J. had

written to my sister in early June, telling her how much he missed me while I

was away. We may still have a copy of the videotape that was made during this

trip, in which case I will see if I can digitize the Ethiopia bits and get them

online.

So: malaria. It turns

out that the Anopheles mosquito, the

one that hosts the malaria parasites, doesn’t live at high elevations. In Addis

Abeba we were over 7500 feet, which is high by any standard, and this was both

a drawback and a benefit for us. For example, water boils at about 198 degrees

at that elevation, which means we had to boil our drinking water for several

minutes to sterilize it. Baking was always a challenge, and not just because we

were working with a finicky gas oven. Whenever we left town we ran the risk of

developing a nasty altitude headache when we got back home. BUT – unlike most

of our colleagues who worked in Africa – we did not have to take anti-malarial

medication on the regular, and that more than made up for any inconveniences.

Our anti-malarial

arsenal at the time included two drugs, chloroquine and mefloquine. According

to Wikipedia, when chloroquine was first discovered in the 1930s, it was

ignored for a decade because it was considered too toxic for human use. Potential

side effects include muscle damage, loss of appetite, diarrhea, skin rash,

problems with vision, and seizures. The common side effects of mefloquine,

which was only approved for prophylactic use in 1989 (!!!), include vomiting,

diarrhea, headaches, and a rash – but it also has potentially long term

neurological side effects including seizures and mental illness. We knew none

of this. We were encouraged to use the drugs in combination when we left the

capital to make sure were we protected against different strains of malaria.

Our Ethiopian colleagues

were just as vulnerable to malaria as we were, but they used different

prophylactic tactics. The most common of these was an aerosol pesticide spray –

Mobil brand, like the gas station – that they deployed liberally before they

went to bed. My memories of those first visits to Cheha include sleeping (or

trying to sleep) in a hot, airless, pitch-black room in a cinder block building,

breathing in the petro-floral scent of Mobil spray. Waking up in that room was

like waking in a tomb, dark and disorienting. There was no electricity, of

course, and we had to keep the window shutter closed because there was no glass

or screen or net to keep the mosquitoes away while we slept; after all, the very

best way to prevent malaria is not to be bitten. And we didn’t get malaria; at

least, not on that trip. That, I would have remembered!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)